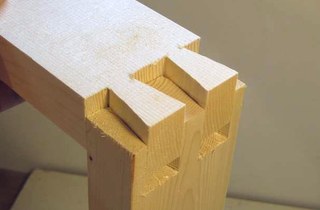

Dovetail joint vs box joint

Comparing the strength of a dovetail joint to a box joint

On a visit to Busy Bee Tools,

I noticed they had a dovetail jig for just $50. I had been thinking of buying

a dovetail jig for some time, and for that price, I figured it was worth a try.

It turned out, I still needed the router template bushing set, but I managed to get

one of those for $12 at The Home Depot.

On a visit to Busy Bee Tools,

I noticed they had a dovetail jig for just $50. I had been thinking of buying

a dovetail jig for some time, and for that price, I figured it was worth a try.

It turned out, I still needed the router template bushing set, but I managed to get

one of those for $12 at The Home Depot.

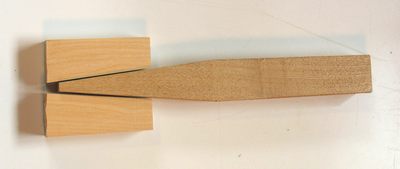

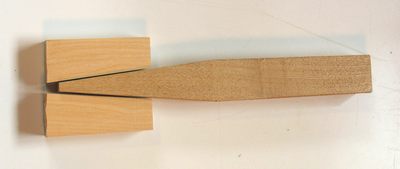

I made a few test joints until I got the adjustments right. Getting a dovetail joint

that really fits is quite satisfying, especially the way it locks together even without

glue.

I made a few test joints until I got the adjustments right. Getting a dovetail joint

that really fits is quite satisfying, especially the way it locks together even without

glue.

But now what? I felt that

making dovetail joints with this jig was perhaps a bit much work, and is it really worth

using dovetail joints? So I decided to do a test joint of a dovetail joint vs my

favourite kind of joint for corners - the old fashioned box joint.

But now what? I felt that

making dovetail joints with this jig was perhaps a bit much work, and is it really worth

using dovetail joints? So I decided to do a test joint of a dovetail joint vs my

favourite kind of joint for corners - the old fashioned box joint.

The advantage of a box joint is that it can be cut on the table saw with a dado blade.

Once set up, this goes much faster. Plus, you can cut a whole stack of work pieces

all at once, so when making a number of box joints, things go relatively quickly.

The advantage of a box joint is that it can be cut on the table saw with a dado blade.

Once set up, this goes much faster. Plus, you can cut a whole stack of work pieces

all at once, so when making a number of box joints, things go relatively quickly.

I used my home made tenon jig to make the joint,

because it has enough range of movement to allow doing this (unlike the

Delta jig). The other thing about the home made jig is that the screw has 10 turns

per inch, so to space the 1/4" wide cuts 1/2" apart, was just a matter of turning five

turns between the successive fingers.

I used 1/4" fingers, whereas the dovetails are 1/2" wide. I figured this was only fair

seeing that the box joint is still much quicker to cut at that spacing. (Update:

I hav since built fancy box joint jig that can

cut this joint even better.

I stacked three pieces - the two halves of the joint, plus a scrap piece to avoid

tearout, and cut them all at once.

I tested the joints by pressing the box apart from the inside.

I used three wedges on the inside of the box to force it apart.

I tested the joints by pressing the box apart from the inside.

I used three wedges on the inside of the box to force it apart.

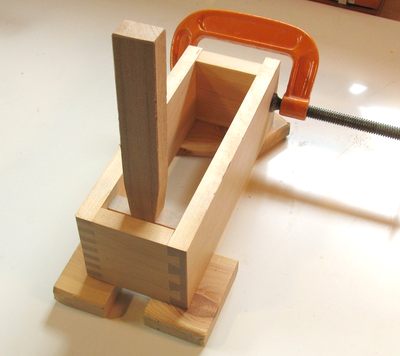

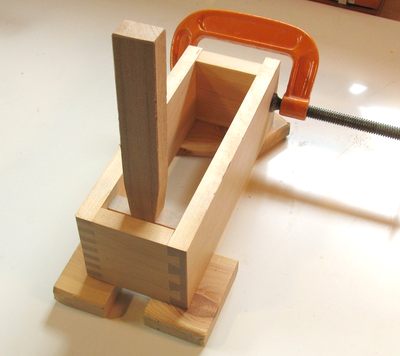

And here is the test setup, with the wedges in the box. The back of the box has no joint at all,

just a spacer and a C clamp to keep the box from folding open.

I wanted to test the joints for pull apart. The idea was to test the dovetail joint

in the direction that its strongest in.

And here is the test setup, with the wedges in the box. The back of the box has no joint at all,

just a spacer and a C clamp to keep the box from folding open.

I wanted to test the joints for pull apart. The idea was to test the dovetail joint

in the direction that its strongest in.

It took some surprisingly vigorous pounding on the wedge to cause one of the joints to fail.

I started by pounding the wedge with a wooden mallet, but switched to a heavier steel hammer

before I got the joint to budge. Really, both of these joints are quite strong.

It took some surprisingly vigorous pounding on the wedge to cause one of the joints to fail.

I started by pounding the wedge with a wooden mallet, but switched to a heavier steel hammer

before I got the joint to budge. Really, both of these joints are quite strong.

But as you can see, the dovetail joint is the one that failed first.

The way the joint failed is that the dovetail part of the pins simply sheared off. So the

wood itself, not the glue ended up failing.

The way the joint failed is that the dovetail part of the pins simply sheared off. So the

wood itself, not the glue ended up failing.

The dovetail had the disadvantage of having fewer fingers than the box joint and not

having the fingers go all the way through the piece of wood. Of course, if I had made a box

joint which exactly the same contact area as the dovetail joint, the dovetail joint

would most likely have won. But the thing is, it's so much easier to make

box joints go all the way through.

For this test, the box joint proved stronger. Plus, the box joint is strong in both directions,

whereas the dovetails are useful only for pulling from one piece, but not the other.

So really, to use a dovetail joint for the sake of strength is obsolete, mostly on account of

the strength of wood glues.

I think the main reason to use dovetail joints nowadays is for their looks.

Fact is, for drawers, I have mostly just used nailed rabbet joints which are not nearly as strong

as either joint, and I have never had one fail. I think dovetail joints made a lot more

sense in historic times, before you could really count on woodg glue to hold things together.

On a visit to Busy Bee Tools,

I noticed they had a dovetail jig for just $50. I had been thinking of buying

a dovetail jig for some time, and for that price, I figured it was worth a try.

It turned out, I still needed the router template bushing set, but I managed to get

one of those for $12 at The Home Depot.

On a visit to Busy Bee Tools,

I noticed they had a dovetail jig for just $50. I had been thinking of buying

a dovetail jig for some time, and for that price, I figured it was worth a try.

It turned out, I still needed the router template bushing set, but I managed to get

one of those for $12 at The Home Depot.

I made a few test joints until I got the adjustments right. Getting a dovetail joint

that really fits is quite satisfying, especially the way it locks together even without

glue.

I made a few test joints until I got the adjustments right. Getting a dovetail joint

that really fits is quite satisfying, especially the way it locks together even without

glue.

But now what? I felt that

making dovetail joints with this jig was perhaps a bit much work, and is it really worth

using dovetail joints? So I decided to do a test joint of a dovetail joint vs my

favourite kind of joint for corners - the old fashioned box joint.

But now what? I felt that

making dovetail joints with this jig was perhaps a bit much work, and is it really worth

using dovetail joints? So I decided to do a test joint of a dovetail joint vs my

favourite kind of joint for corners - the old fashioned box joint.

The advantage of a box joint is that it can be cut on the table saw with a dado blade.

Once set up, this goes much faster. Plus, you can cut a whole stack of work pieces

all at once, so when making a number of box joints, things go relatively quickly.

The advantage of a box joint is that it can be cut on the table saw with a dado blade.

Once set up, this goes much faster. Plus, you can cut a whole stack of work pieces

all at once, so when making a number of box joints, things go relatively quickly.

I tested the joints by pressing the box apart from the inside.

I used three wedges on the inside of the box to force it apart.

I tested the joints by pressing the box apart from the inside.

I used three wedges on the inside of the box to force it apart.

And here is the test setup, with the wedges in the box. The back of the box has no joint at all,

just a spacer and a C clamp to keep the box from folding open.

I wanted to test the joints for pull apart. The idea was to test the dovetail joint

in the direction that its strongest in.

And here is the test setup, with the wedges in the box. The back of the box has no joint at all,

just a spacer and a C clamp to keep the box from folding open.

I wanted to test the joints for pull apart. The idea was to test the dovetail joint

in the direction that its strongest in.

It took some surprisingly vigorous pounding on the wedge to cause one of the joints to fail.

I started by pounding the wedge with a wooden mallet, but switched to a heavier steel hammer

before I got the joint to budge. Really, both of these joints are quite strong.

It took some surprisingly vigorous pounding on the wedge to cause one of the joints to fail.

I started by pounding the wedge with a wooden mallet, but switched to a heavier steel hammer

before I got the joint to budge. Really, both of these joints are quite strong.

The way the joint failed is that the dovetail part of the pins simply sheared off. So the

wood itself, not the glue ended up failing.

The way the joint failed is that the dovetail part of the pins simply sheared off. So the

wood itself, not the glue ended up failing.

Dovetail joints

Dovetail joints Dovetail joints

Dovetail joints

Testing mortise and tenon

Testing mortise and tenon