Mortise and tenon vs. dowel joints: A strength test

Some years ago, I had a discussion with a woodworker friend whose opinion I

respect. He argued, quite convincingly, that dowel joints are stronger than

mortise and tenon joints.

His argument was simply that when you assemble a typical tight mortise and tenon joint,

you actually end up scraping most of the glue away from the cheeks of the tenon

in the process of assembling it, and that dowel joints were much less afflicted

in this regard.

Having built a workbench, and a

lathe stand out of 2x4's, the former with

dowel joints and the latter with mortise and tenon joints, I was also wondering which

is the better choice in terms of strength.

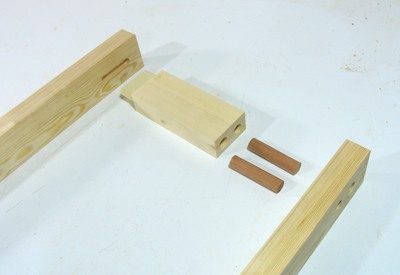

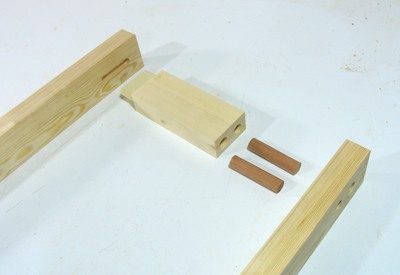

So I build a test frame to test this with. I joined one side with a mortise and tenon

joint and the other with a dowel joint. I made my tenon 1/2" thick, and used

5/8" dowels on the other side. The frame was made of spruce, the dowels out of oak.

I figured it only made sense to use slightly bigger dowels than the tenon I used.

If the dowels were no bigger than the mortise and tenon joint, I was pretty sure

the mortise and tenon would win.

So I build a test frame to test this with. I joined one side with a mortise and tenon

joint and the other with a dowel joint. I made my tenon 1/2" thick, and used

5/8" dowels on the other side. The frame was made of spruce, the dowels out of oak.

I figured it only made sense to use slightly bigger dowels than the tenon I used.

If the dowels were no bigger than the mortise and tenon joint, I was pretty sure

the mortise and tenon would win.

I made sure everything fit well, and glued it all together with plenty of yellow

glue (the water based kind), and let it dry for 18 hours.

After letting it dry, I put the frame on the floor and stepped on the

far end of the legs to break it. The frame was able to hold my weight

standing on it, but with some bouncing up and down on it,

I was able to get it to break.

After letting it dry, I put the frame on the floor and stepped on the

far end of the legs to break it. The frame was able to hold my weight

standing on it, but with some bouncing up and down on it,

I was able to get it to break.

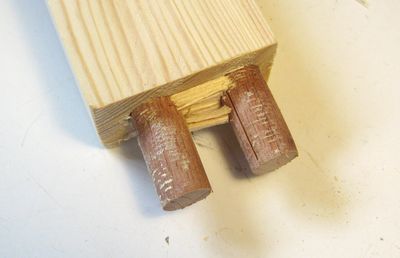

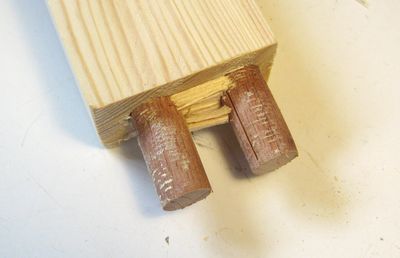

The dowel joint failed first, with the dowels pulling out of the 'leg'.

The failure was mostly along the glue joint between the dowel and the leg.

The dowel joint failed first, with the dowels pulling out of the 'leg'.

The failure was mostly along the glue joint between the dowel and the leg.

Once the glue bond was broken, I used a hammer to separate the joint the

rest of the way to see what was left. I was a bit disappointed to see how

cleanly the joint had failed along the glue surface, and was thinking perhaps the

yellow glue that I use is not nearly as strong as the wood.

Once the glue bond was broken, I used a hammer to separate the joint the

rest of the way to see what was left. I was a bit disappointed to see how

cleanly the joint had failed along the glue surface, and was thinking perhaps the

yellow glue that I use is not nearly as strong as the wood.

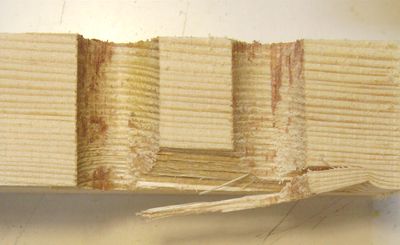

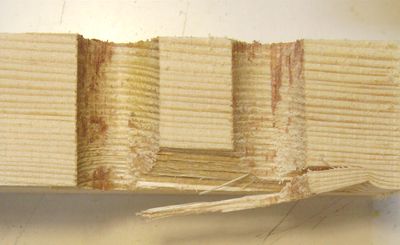

I cut the dowel joint open with a bandsaw to look inside. Interestingly enough, there

were thin slivers of oak dowel that remained stuck inside the joint. And looking

closely at the oak dowels, they also had tiny bits of the spruce still stuck to them.

So even though the joint had failed along the glue line, it was actually

the wood that let go in many spots.

I cut the dowel joint open with a bandsaw to look inside. Interestingly enough, there

were thin slivers of oak dowel that remained stuck inside the joint. And looking

closely at the oak dowels, they also had tiny bits of the spruce still stuck to them.

So even though the joint had failed along the glue line, it was actually

the wood that let go in many spots.

My thinking is that even if the glue was much stronger than the wood, it's the grain

discontinuity of the joint itself that may cause it to fail right there.

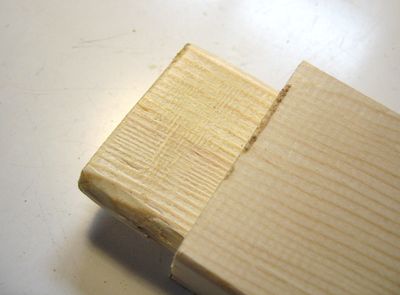

I also ended up hammering the mortise and tenon joint apart to see how it would fail.

That took a fair bit more effort than getting the dowel joint apart.

I also ended up hammering the mortise and tenon joint apart to see how it would fail.

That took a fair bit more effort than getting the dowel joint apart.

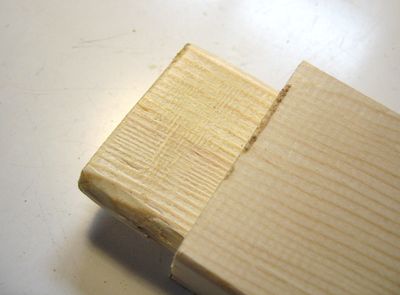

This joint too failed right at the glue line. Looking at the extracted tenon,

you can see fibers from the mortise stuck to it.

I cut the mortise open with a band saw, and it too had evidence of bits of the tenon

stuck to it. In fact, it seems that for any part of the joint, fibers either got

transferred from the mortise to the tenon, or vice versa.

I cut the mortise open with a band saw, and it too had evidence of bits of the tenon

stuck to it. In fact, it seems that for any part of the joint, fibers either got

transferred from the mortise to the tenon, or vice versa.

So even though the joint failed at the glue line, this test suggests that the

glue is about as strong as the wood.

So my conclusion is that in this example, the mortise joint is stronger than the dowel

joint, even if the dowels are thicker than the mortise would be. Of course, there are

many parameters that could be varied to make a difference, but with hardwood

dowels larger than my tenon, I figure I did give the dowel joint a bit of an advantage.

That said, even if the tenon joint had failed first, I would still continue using

mortise and tenon joints, because I am well set up for making

mortise and tenon joints, and I find it easier to get

them really precise.

So I build a test frame to test this with. I joined one side with a mortise and tenon

joint and the other with a dowel joint. I made my tenon 1/2" thick, and used

5/8" dowels on the other side. The frame was made of spruce, the dowels out of oak.

I figured it only made sense to use slightly bigger dowels than the tenon I used.

If the dowels were no bigger than the mortise and tenon joint, I was pretty sure

the mortise and tenon would win.

So I build a test frame to test this with. I joined one side with a mortise and tenon

joint and the other with a dowel joint. I made my tenon 1/2" thick, and used

5/8" dowels on the other side. The frame was made of spruce, the dowels out of oak.

I figured it only made sense to use slightly bigger dowels than the tenon I used.

If the dowels were no bigger than the mortise and tenon joint, I was pretty sure

the mortise and tenon would win.

After letting it dry, I put the frame on the floor and stepped on the

far end of the legs to break it. The frame was able to hold my weight

standing on it, but with some bouncing up and down on it,

I was able to get it to break.

After letting it dry, I put the frame on the floor and stepped on the

far end of the legs to break it. The frame was able to hold my weight

standing on it, but with some bouncing up and down on it,

I was able to get it to break.

The dowel joint failed first, with the dowels pulling out of the 'leg'.

The failure was mostly along the glue joint between the dowel and the leg.

The dowel joint failed first, with the dowels pulling out of the 'leg'.

The failure was mostly along the glue joint between the dowel and the leg.

Once the glue bond was broken, I used a hammer to separate the joint the

rest of the way to see what was left. I was a bit disappointed to see how

cleanly the joint had failed along the glue surface, and was thinking perhaps the

yellow glue that I use is not nearly as strong as the wood.

Once the glue bond was broken, I used a hammer to separate the joint the

rest of the way to see what was left. I was a bit disappointed to see how

cleanly the joint had failed along the glue surface, and was thinking perhaps the

yellow glue that I use is not nearly as strong as the wood.

I cut the dowel joint open with a bandsaw to look inside. Interestingly enough, there

were thin slivers of oak dowel that remained stuck inside the joint. And looking

closely at the oak dowels, they also had tiny bits of the spruce still stuck to them.

So even though the joint had failed along the glue line, it was actually

the wood that let go in many spots.

I cut the dowel joint open with a bandsaw to look inside. Interestingly enough, there

were thin slivers of oak dowel that remained stuck inside the joint. And looking

closely at the oak dowels, they also had tiny bits of the spruce still stuck to them.

So even though the joint had failed along the glue line, it was actually

the wood that let go in many spots.

I also ended up hammering the mortise and tenon joint apart to see how it would fail.

That took a fair bit more effort than getting the dowel joint apart.

I also ended up hammering the mortise and tenon joint apart to see how it would fail.

That took a fair bit more effort than getting the dowel joint apart.

I cut the mortise open with a band saw, and it too had evidence of bits of the tenon

stuck to it. In fact, it seems that for any part of the joint, fibers either got

transferred from the mortise to the tenon, or vice versa.

I cut the mortise open with a band saw, and it too had evidence of bits of the tenon

stuck to it. In fact, it seems that for any part of the joint, fibers either got

transferred from the mortise to the tenon, or vice versa.

Mortise and tenon joinery

Mortise and tenon joinery Dowel joinery

Dowel joinery Testing different types of joints

Testing different types of joints Mortise and tenon vs dowel joint revisited

Mortise and tenon vs dowel joint revisited Testing the strength of wood glues

Testing the strength of wood glues